Skilled Labor Series: Firefighting

*This episode is part of our Skilled Labor Series hosted by MCJ partner, Yin Lu. This series is focused on amplifying the voices of folks from the skilled labor workforce, including electricians, farmers, ranchers, HVAC installers, and others who are on the front lines of rewiring our infrastructure.

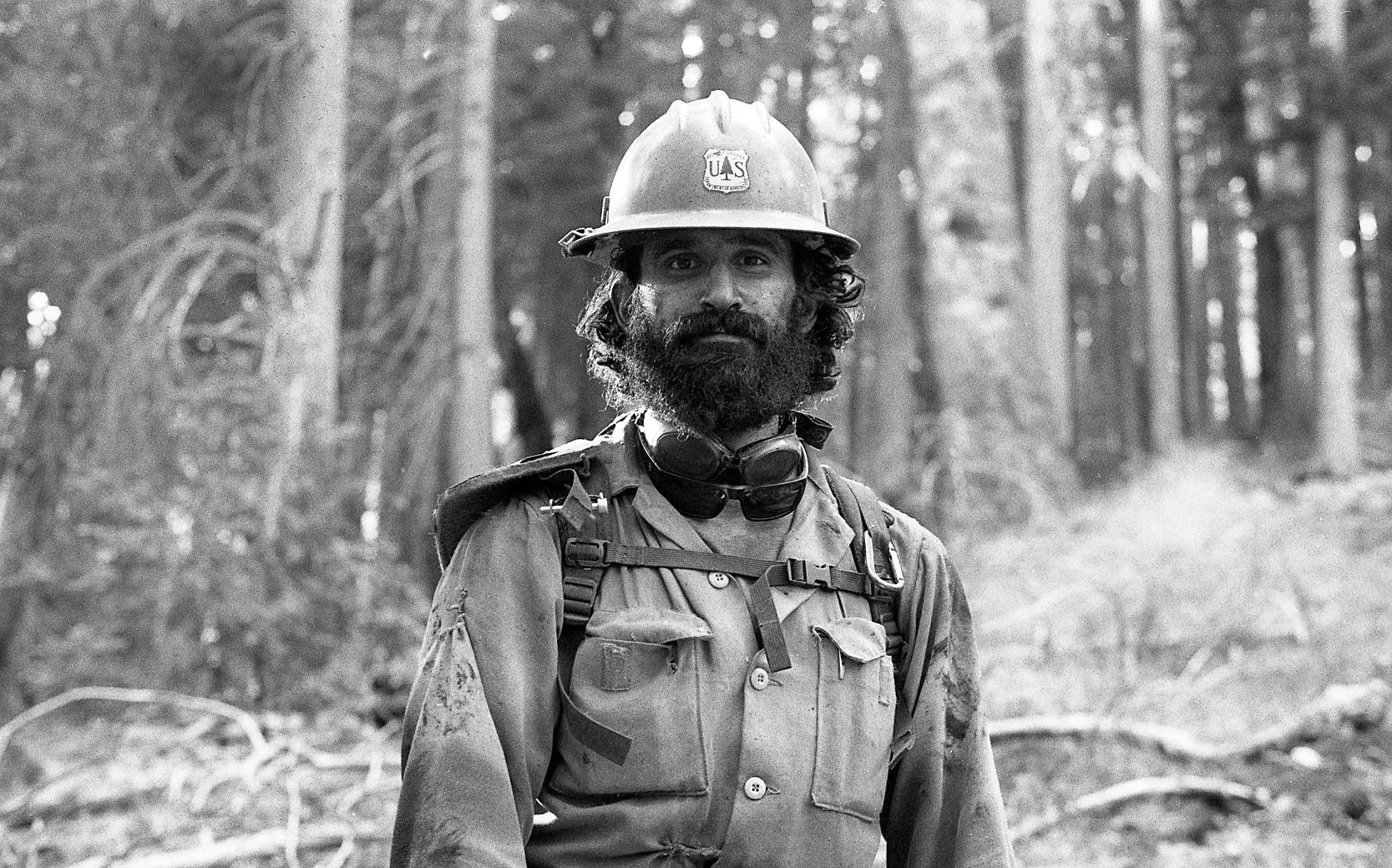

Today's guest is James Sedlak, who leads Operations and Community Engagement at Kodama Systems, a startup developing automated ways of thinning overcrowded forests and utilizing low-value biomass, which we'll learn more about in the episode.

From 2019 to 2021, James was a wildland firefighter for three seasons working on fire suppression and mitigation in the El Dorado National Forest. He has also worked on climate resilience projects for local and state agencies in California, such as the Governor's Office of Planning and Research, and the Tahoe Conservancy.

In this episode, we get into the nitty-gritty of the day of the life of a wildland firefighter and learn about the future of firefighting and what the space will entail. After hearing about the dedication and dangers associated with wildland firefighting, you’ll walk away with a much deeper appreciation and gratitude for the work being done around the mitigation and suppression of fires. And lastly, we at MCJ Collective are proud to be investors in Kodama via our venture capital funds. Enjoy the show!

Get connected:

Yin’s Twitter / LinkedIn

MCJ Podcast / Collective

*You can also reach us via email at info@mcjcollective.com, where we encourage you to share your feedback on episodes and suggestions for future topics or guests.

Episode recorded onJanuary 15, 2022.

In this episode, we cover:

[2:00] James' background and how he landed his current role at Kodama

[5:43] An overview of the El Dorado National Forest and James' work in wildland fire

[7:04] Different types of firefighting and how to get started

[10:31] Courses and the interview process

[12:02] Career progression for working in the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service (USFS)

[17:51] An overview of hotshots

[19:27] What it's like to be a firefighter and the typical experience during a fire season

[22:41] The importance of pre-season training and supporting mental health programs for firefighters

[26:43] Challenges with retention in the federal wildland firefighting workforce

[28:21] An overview of mitigation suppression to prevent wildfires

[30:27] Wildfire trends from out on the frontlines and within the workforce

[32:49] James' work at Kodama

[38:01] Implications of recent flooding on the fire season for this year and years to come

-

Jason Jacobs (00:01):

Hello, everyone. This is Jason Jacobs.

Cody Simms (00:04):

I'm Cody Simms.

Jason Jacobs (00:05):

Welcome to My Climate Journey. This show is a growing body of knowledge focused on climate change and potential solutions.

Cody Simms (00:15):

In this podcast, we traverse disciplines, industries, and opinions to better understand and make sense of the formidable problem of climate change and all the ways people like you and I can help.

Jason Jacobs (00:26):

We appreciate you tuning in, sharing this episode, and if you feel like it, leaving us a review to help more people find out about us so they can figure out where they fit in addressing the problem of climate change.

Yin Lu (00:40):

Hey, everyone, Yin here. I'm a partner at MCJ Collective and I host this podcast series called The Skilled Labor Workforce, where we amplify the voices of people who are on the front lines of rewiring our physical infrastructure. Today's guest is James Sedlak, who currently leads operations and community engagement at Kodama Systems, a startup developing automated ways of thinning overcrowded forests and utilizing low value biomass, which we'll learn more about in the episode. From 2019 to 2021, James was a wildland firefighter for three seasons working on fire suppression and mitigation in the El Dorado National Forest. He has also worked on climate resilience projects for local and state agencies in California, such as the Governor's Office of Planning and Research, and the Tahoe Conservancy. In this episode, we get into the nitty-gritty of the day of the life of a wildland firefighter and learn about the future of what firefighting will entail. This conversation has made me so much more deeply appreciative and grateful of the work being done around mitigation and suppression of fires. Buckle in. This is a good one. With that, James, welcome to the show.

James Sedlak (01:43):

Thank you, Yin. I really appreciate it, and it's an honor to be on the show.

Yin Lu (01:47):

All right, so let's dive in. We have a lot to learn about you as a person and what you do as a profession. First things first, tell us a bit more about you. Who are you, where did you grow up, and how did you find your way to become a wildland firefighter?

James Sedlak (02:02):

Oh, wow. Yeah, that's a loaded question. I'll start by saying, currently, I work at Kodama Systems, leading their operations and community engagement, and I joined working for Kodama because I'm passionate about working in natural resources and making a big impact with my work. I am relatively, I would say, new to the West Coast. I moved out here about four and a half years ago with the purpose of getting a job in wildland firefighting. After college, I worked in New York City for a few years as a paralegal, thinking I would go to law school, but realized that wasn't really what I wanted to do, so I took some time off to travel. On that journey, I reconnected with nature and felt a new calling to do some kind of public service, and remember reading about new career paths and stumbling upon what wildland firefighting was and felt like it was the perfect marriage of public service and working in nature, and so when I got home from traveling, I packed up all my bags from the East Coast right outside New York City and moved out west to get a job in wildland fire.

Yin Lu (03:12):

And bid farewell to a potential legal career and going to law school, or is that maybe still on the books as some later point?

James Sedlak (03:19):

Oh, no, it was long forgotten. Right when I hit Route 80 and I crossed from New Jersey to Pennsylvania, I didn't think about it again.

Yin Lu (03:26):

I'm so curious on your travels. Were there certain points that really cemented in you how important it was to work in forestry?

James Sedlak (03:33):

It was just a nerve-wracking journey, and throughout the drive and the process, I was nervous about the application process and meeting all these potential crews, and hiring officers, and interviewing along the drive out west, but at the same time, I felt some kind of reconfirmation that this was the right path as I was driving through all these beautiful natural landscapes and taking it all in. I felt like a really good new chapter for me.

Yin Lu (04:02):

When you look back on your childhood, I'm going to ask what feels like a stereotype. Did you play with firetrucks? Was there some seed in you from an early age that made you attracted to doing this type of work?

James Sedlak (04:14):

Not really. I grew up outdoors going camping and hiking, and I had a typical appreciation for the outdoors and having fun. I learned early on some really good principles about taking care of the land and being a good steward from some certain role models in my life, so I think that always stuck with me.

Yin Lu (04:34):

All right. Very cool. Now, you're driving across the country, you land in Northern California, what happens next?

James Sedlak (04:40):

Oh, wow. I got to California, and first thing on the way out here, I took a job in Oregon because people that I networked with said, "If you get a job, take it because it's hard to get your foot in the door," and so I took a job in Oregon, but then I met who was now my fiance at a ski lease in Lake Tahoe along the way. She was a special person then, and I figured it was important to try to stay around California, so I ended up getting a job on the El Dorado National Forest, which was a lot closer to her in San Francisco and Lake Tahoe.

Yin Lu (05:16):

Got it. So, you drove and then you took a job in Oregon, and then came down to Tahoe thinking, "Maybe I'll stay in Oregon," and then you met this person who is, and we should say it's T minus a couple of weeks before your wedding at the time of this recording, and so you decided, "I met a person. I'm going to stick around in California," instead of ending up in somewhere else?

James Sedlak (05:37):

Yeah, pretty much.

Yin Lu (05:38):

Nice. For those who don't know about the El Dorado Forest, where is it and how big is it?

James Sedlak (05:43):

Yeah, the El Dorado National Forest is located in the Sierra Nevada mountains in California. It's sandwiched in between Route 80 and Route 50 in between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe. It's about 600,000 acres, I want to say.

Yin Lu (06:00):

Okay. There's a real amount of land. How big of a crew is needed to cover that entire area? Is there some type of ratio between a number of people to acreage?

James Sedlak (06:11):

I don't think there's an exact ratio, but typically, national forests are split up into ranger districts, and each ranger district has a certain amount of resources and crews that it staffs up. As far as crew goes, there are different crews from your typical forestry technician crews, there's range management and monitoring, there's wildland fire, there's other recreation crews, there's other patrols, so yeah, there are a lot of different personnel that work on the different districts.

Yin Lu (06:45):

Okay, and maybe we should take a step back. Certainly would be helpful for me to... When we talk about firefighting as a profession in general, there's what we think about the red trucks in the cities and then there's what you do. Maybe help us distinguish the different types of firefighting categories there are, and then we'll deep dive on the wildland firefighting.

James Sedlak (07:04):

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, like you said, there's city and structure fire that typically work in municipal governments and cities and towns, and then there's your wildland fire crews that have those ugly green trucks and engines, and there are also private crews out there that make up part of the workforce. You typically have a split between your city and structure, and then your strictly wild land, although there are plenty of city and structure fire crews that do wild land firefighting or are capable of it.

Yin Lu (07:41):

A scenario there would be there's a huge fire that is adjacent to Santa Cruz, California, and we don't have enough people, so we'll bring in some of the structured or municipal firefighting capacity to help out.

James Sedlak (07:53):

Yep.

Yin Lu (07:54):

Gotcha. Then private crews? Can you talk about that a bit? Definitely something new I'm learning. Is it also just the supplementing capacity when needed?

James Sedlak (08:03):

Yeah, I think private wildland firefighting crews are sometimes used for just private landowner projects or fires, although that's a touchy subject because there's liabilities and other complications involved with that, but a lot of times, we will see private crews on some of the federal and state incidents that my crew was on, so they get a fair share of work during fire season on federal and statewide wildfires.

Yin Lu (08:33):

Cool. Thank you for educating me on that aspect of the industry. Let's jump back into wildland firefighting. How do you get started in a job like that if you have zero baseline knowledge and a passion for wanting to do this work?

James Sedlak (08:49):

Yeah, that's a great question. I started out by just calling all of the hiring officers I could find online and just asking them for time to teach me about how to go about the job application process, which can be actually challenging, especially navigating the federal, and I'm talking just wildland firefighting from a federal perspective working for the Forest Service or some of the other agencies like Bureau of Land Management, Department of Fish and Wildlife, National Park Service. They all have wildland firefighting crews.

Yin Lu (09:25):

You spent three seasons working for the US Forestry Service, correct, as the federal agency?

James Sedlak (09:29):

Yeah, the Forest Service. I'll just say to get a job with the Forest Service, you have to go through USAJOBS, which is their hiring platform, which is cumbersome. If you check the wrong box, then you could just disqualify yourself from a job application even though it's just a formality, so things like that. I was coached up on that and I took my time learning USAJOBS, and then through some networking, I was told if I want to work in wildland firefighting, I better start working out and try to do some basic courses. I think it's called Basic 40 nowadays. It's your typical entry level classes that teach you things about fire and operational safety, like fire behavior, communications and situational awareness, like your intro to wildland firefighting.

Yin Lu (10:24):

Then what happens after you take those courses? Is there an interview process? What does that interview process entail?

James Sedlak (10:31):

Yeah, so I took my course in Salida, Colorado. Forget the name of the fire camp it was. I took my course and that was right after I had applied to all of these positions through USAJOBS. Then the next best thing you can do is go meet the crews and hiring officers that you applied to, and get to know them, and let them meet you face to face. That's what I did. Then I ended up meeting with the engine captain on the El Dorado National Forest where I took my first job, and after a couple of more months of waiting to hear back, they offered me position, and I took it.

Yin Lu (11:11):

Is there a formalized interview process where you're sitting down, they're asking you questions, and how you respond and how you behave in certain settings? Is there maybe a physical component where they say, "Put out this fire in as little time as possible"? Is there something like that?

James Sedlak (11:23):

There is no real in-person test to trial your firefighting skills, but in your resume, you're told to put any and all information about any of those skills that could be used, and so that gives them a pretty good picture of your background. The interview process is, I think, it was one or two phone calls. They ask you typical set of questions about how you deal with stress in certain situations, and what your working style is like, and your typical interview questions. Nothing too specific about wildland fire.

Yin Lu (11:57):

Gotcha. They also have the record of your taking those courses and your performance in those courses as well to go off of?

James Sedlak (12:02):

Yes.

Yin Lu (12:02):

Very cool. Well, glad that you hit the gym and were able to be in top physical condition to be able to start the role. What does career progression look like for USFS for doing firefighting? Do you start off only being able to do certain types of things and then where do you graduate to?

James Sedlak (12:22):

Yeah, I think it really depends on where you're interested in or what direction you want to go. I'll say you just typically start off as what's called a GS3, and that's just the occupational series and grade entry level is a GS3 employee. As an entry level employee, you're coming in at a GS3 making somewhere, it might now be around $15 an hour, and you go through a training program with your crew, and you learn up on all the things that you need to know to be a good team player on that crew, and then you can start opening up what's called a task book. A task book allows you to pursue different qualifications and certifications within your wildland fire career. You typically have to work towards completing your task book by doing things out in the field on incidents under supervision.

(13:21):

The next task book that I opened was... I came in as a GS3, but my qualification was a Wildland Firefighter Type 2, and so my next step up would be a Wildland Firefighter Type 1, so you open up that task book and then you go through a whole bunch of different assignments and tasks that you have to do under supervision, like leading a small squad of firefighters on an incident, doing necessary paperwork, there's a variety of things. Then from there, after you get your Firefighter 1, you can look into more or higher leadership positions like becoming a squad boss and then maybe a captain superintendent. Then aside from that, there are different qualifications within those rankings, like you can open a task book to become a certain incident commander for a certain size of a fire or incident. It would be IC5 is your smallest fire that you can be in charge of, and you're the one ordering resources from dispatch, calling the shots, and managing crews.

(14:29):

That goes up to being a Level 1 Incident Commander that's in charge of some of these huge fires with thousands of personnel that are really complex. There's a steady progression. Overall, these qualifications, they take time, especially as you get further into your career and sometimes to level up. Say if you get the qualification, but if you want to apply for say the next pay grade, say from a GS4 to a 5 or a GS5 to a 6, sometimes there's no position available on your crew or to apply for, so sometimes there could be some stagnation and it could be competitive getting certain positions or qualifications.

Yin Lu (15:12):

Fascinating. It sounds like we got the whole enchilada, the quick and dirty version of the whole enchilada on career progression within wildland firefighting. In your three seasons as a wildland firefighter, where in that career progression were you wanting to get to? Tell us about the role that you had most recently before you left.

James Sedlak (15:28):

Yeah, so I initially entered the Forest Service with the aspiration of becoming a smoke jumper. Smoke jumpers, for anyone who doesn't know, is they're like the Navy SEALs of wildland firefighting. They get deployed to very remote fires by airplane. They jump, hence their name smoke jumpers, they jump out of planes, parachute into fires, and they're fully self-sufficient, and they run their own show. Typically, they work in small teams, but also, they work on other wildfire incidents as well. To me, that just seemed like the top of the top to push for.

Yin Lu (16:04):

How long would it take for someone to start off at a GS3 entry level to becoming a smoke jumper?

James Sedlak (16:09):

It could take only a few seasons depending on how well you do and if you have the right qualifications. I believe rookie smoke jumpers, they can be GS5. I think that might the lowest GS level, so shorter than you might think. I came into the Forest Service with that goal, and my first job was with a Type 3 engine on the El Dorado National Forest. A crew of five people are rotating, five to six people, that basically work with this small fire truck with 500 to maybe 600 gallons of water. We did a lot of suppression assignments, implementing hose lays, and using water to put out the fire. While on that crew, we also served as the first response for our local ranger district, so that was in Georgetown, California. If there was a vehicle accident somewhere along those remote roads, we were typically dispatched as the first emergency medical response.

(17:16):

After that first season of working as, technically, a forestry aid is the entry level terminology, I'd talked to my captain and I asked him, I was like, "Hey, I'd really be interested in trying out for the El Dorado hotshot crew," and he put me in touch with their superintendent and the captains, and it didn't work out where I tried out for them that year, but the following year, I applied to be on the crew and then I met with them, interviewed, and things went well enough for them to bring me on board.

Yin Lu (17:49):

What does hotshot mean?

James Sedlak (17:51):

I think hotshot actually gets its name because traditionally, this type of wildland firefighter or the crew has gone into the hottest parts of the fire and done the hardest work, but to me, hotshots are elite groups or highly skilled groups of 20 wildland firefighters that are very well-trained in vegetation management with hand tools, burning operations, and their critical resources for managing wildfires.

Yin Lu (18:20):

We're going to take a quick break so you can hear me talk more about the MCJ membership option. Hey, folks, Yin here, a partner at MCJ Collective. Want to take a quick minute to tell you about our MCJ membership community, which was born out of a collective thirst for peer-to-peer learning and doing that goes beyond just listening to the podcast. We started in 2019 and have since then grown to 2000 members globally. Each week, we're inspired by people who join with differing backgrounds and perspectives. While those perspectives are different, we all share in common is a deep curiosity to learn and bias to action around ways to accelerate solutions to climate change. Some awesome initiatives have come out of the community.

(18:57):

A number of founding teams have met, nonprofits have been established, a bunch of hiring has been done, many early stage investments have been made as well as ongoing events and programming like monthly Women in Climate meetups, idea jam sessions for early stage founders, climate book club, art workshops, and more. Whether you've been in climate for a while or just embarking on your journey, having a community to support you is important. If you want to learn more, head over to mcjcollective.com and click on the members tab at the top. Thanks and enjoy the rest of the show.

(19:27):

All right, let's get back to the show. I think this is a good jumping off point to talking about the day-to-day on the job and what that's like. I'm sure there's no same day-to-day in the type of work that you do with the people that you do it with, and so maybe just talk to us about what it's like in a season and maybe help us define what does it mean by a fire season?

James Sedlak (19:48):

Yeah, sure. I'll start off by saying, typically, what was the case when I was working for the Forest Service, fire season in California at least was starting in May through November. Basically, the snow pack melts, things get dry, and things are typically, they're ripe for fires around May, June, and then we don't get a lot of precipitation until around November. That was your fire season. Nowadays, it's looking more like fire year, especially in southern California and other parts of the US. Things are still dry going into January, February even, so the threat of wildfire lingers throughout the year or for most of the year. When you come on in May, you've got two weeks of critical training where it's just really intense hiking, pushing the limits, and training the crew up to be in the best shape that they can be to basically have six, seven months of nonstop firefighting.

(20:48):

Almost all of our work or time was spent on wildfire suppression. We would go to incidents mostly in California, but sometimes, you'd get called up to incidents in different states because as a federal resource, you can be deployed all over the country. I think we went up to Alaska, down to Arizona, over to Idaho. During fire season, you're traveling around working on fires for two, maybe three weeks at a time, and then pulling shifts. Your typical shifts were 14 to 16 hours, and then you're expected just to get your eight hours of sleep, and then return, repeat, do it all again, but sometimes, shifts, they extend into the wee hours of the night that can run 24 even more hours depending on the situation and what you have to do during that time to meet your objectives and make progress.

(21:44):

Over the span of two to three weeks, typically two weeks, on an assignment or on a fire, you could have some really crazy shifts or you have some normal shifts. It all depends, but overall, you're going through this process of two weeks out on fire assignments. You get two to three days off at home to rest and recover, they call it R&R, and then you come back to your crew or your station, and then in the height of fire season, you typically have another resource order that calls your crew onto another fire. It's that on repeat for six months or so.

Yin Lu (22:24):

Oh, my God. I was going to ask you a question about what are some of the things that wildlife firefighters do that may not seem obvious, and this clearly jumps out as one just how rigorous and intense the role is. Physically, and I'm imagining also just mental health wise, it could take a toll. Tell me more about that.

James Sedlak (22:41):

Sure. That's why pre-season training, getting your body in top shape is really important. That way, you come into your critical training and you're pushed a little further to really be at optimal productivity mode, if you will. You can hike well, you can carry a chainsaw, you can deal with the heat, you can just have a good sustained cardiovascular endurance, things like that. You come into the season in tiptop shape, and then throughout the season, your body just takes a beating. There're obviously physical safety concerns just from doing the arduous work of hiking around, carrying things, you can trip over branches, there are loose rocks and dead trees that fall down, you can get really bad cuts, even bees can be really, I guess, annoying, and you're working around heavy equipment machines on a lot of these fire assignments where things are loud and it's chaotic, and at times, it's dark.

(23:41):

There's just a lot going on, and so there's always these hazards, and so it's super important to keep really good situational awareness. Aside from the physical concerns of the job, the mental hazards and the mental health issues are also really, really important to consider. People that have kids or being away from family can be really tough for a lot of folks. A lot of times, it's tough to balance your responsibilities with your friends and family, and your assumed commitment to the crew because if the crew doesn't have enough numbers for staffing, then it's difficult for them to go to wildfire incidents and do their work. If people can't go to wildfire incidents and work, that's money not getting into their bank accounts and that ends up affecting their livelihoods, and so it's tough.

(24:37):

It's tough to deal with all those stressors. Just the things you might see or deal with, whether it's totally burnt lands, burnt homes, and towns, dead animals, a lot of these things and some of the trauma of near misses, I think, adds to a good amount of PTSD. I think there's, in general, just a much higher rate of suicide among firefighters than the general public. Mental health, I think, is one of those things that hadn't really been talked about for a while, but thankfully recently, there's been a push to support or improve those mental health programs, and a lot of people are stepping up to be leaders in that space and encourage folks to address it.

Yin Lu (25:22):

Well, that was a lot. Thanks for sharing. I have such a deeper appreciation for you all doing the work that you do that I think oftentimes we take for granted, which is assumed that, yes, this fire is eventually going to get put out, but it comes at a cost, it sounds like sometimes a very heavy cost for the people that are actually on the ground doing it. What do you think are a few things that could change the industry for the better so that there's more longevity in staying in a role like this, knowing just how tense it is? Is there just more time off versus time on? What are those mental health resources that you're saying are now coming to front of mind that weren't there before?

James Sedlak (26:00):

Yeah, well, I think for starters, wildland firefighters could get paid more. Given the amount of risk they take on and the hard work that they put in, they ought to be paid more, and that's being addressed right now. I think one of the main bills to address that was the recent infrastructure bill that is increasing pay for wildland firefighters working on reclassifying the job series to better allocate and address the other benefits and these mental health programs. I think there's more legislation in the pipeline. I don't know if it'll pass, but overall, we need to treat this workforce better because not only are we still relying on them, they deserve it.

Yin Lu (26:43):

Yeah, I think that's all that needs to be said. They deserve it 100%. I'm so curious just talking about workforce development some more. From a workforce development angle, what trends had you seen or are you seeing in terms of the volume of workforce coming in, so people that are expressing interest in wildlife firefighting versus people that are treating out of the workforce? Are we seeing a delta of people wanting to come into the industry at all?

James Sedlak (27:12):

I think we're seeing more people leaving, and that's I think primarily because people are getting paid better. When I say leaving, I mean leaving the federal wildland firefighting workforce, and they're leaving to go to state agencies, municipal agencies that will pay better, offer better benefits, perhaps give a slightly adjusted work lifestyle balance. I think overall, from what I recall, it's been difficult for the Forest Service to retain its workforce. I don't get the sense there's a lot of passion or interest to pursue this line of work because of the conditions and the current benefits right now. However, I'm somewhat optimistic that things will change around workforce development because of recent legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act that I think will pump more money into programs to build up our forestry workforce on the suppression side. That's just the suppression side. We're still lacking the workforce to do key mitigation efforts to combat wildfires, but we can get into that.

Yin Lu (28:21):

Let's get into that. What do we mean when we say mitigation suppression? I get fires, we got to put them out, we got to control where they burn. Mitigation means?

James Sedlak (28:29):

Yeah, so mitigation is basically what you could do to prevent wildfires. In my mind, I'm thinking forest thinning treatments, how you deal with community education, home hardening, anything you could do to prevent those basically high intensity fires that are problematic these days. I think the Forest Service recently put out a commitment to treat 50 million acres of land in the next 10 years, but a lot of people are scratching their heads wondering, it's like, "How are we going to get on track for that with such a limited workforce?" We can barely keep up staffing levels for suppression. How are we going to build our labor pool for the mitigation work that so desperately needed to prevent these catastrophic wildfires?

Yin Lu (29:16):

Yeah, so that's good to understand about mitigation being so complimentary to suppression, and proactively, if we can do more on the mitigation side, we'll have hopefully less to do on the suppression side, but who's going to do the work at the end of the day? It sounds like earlier, we were talking about private fire crews, I wonder if more of those might pop up, and the pay dynamics there are better. I just wonder, in general, how can we get more people interested in, sounds like money, is pretty more money, other problem is one solution, and I wonder what else there might be? Do you have any thoughts on that?

James Sedlak (29:46):

Yeah, I think putting more money into workforce development is good and I think we can achieve more results on the mitigation side, treating more acres by developing larger collaboratives, and pulling together different jurisdictions, and really building good partnerships, but I also think there's a lot of good momentum around investing in the private sector and technology innovations that will help work alongside the workforce, especially as we grow to improve those numbers so then we can eventually hit our target of acres treated that we're setting out.

Yin Lu (30:27):

This is a good segue to talking about trends and technology a bit more. I'm so curious to hear your take on technology and trends having been both on the ground working for the federal government as well as working now at a startup that's focused on forest restoration services. I'd love to know, is there anything that you're noticing about fire seasons just looking at trends being on the front lines, first and foremost, on fires that you were fighting three years back to the most recent fires you've been suppressing? Is there difference in the speed at which they're going, et cetera, et cetera?

James Sedlak (31:01):

Yeah, so general trends that I experienced were... Well, I guess it's hard for me to call it a trend because I was out on the front lines for a few seasons, but I noticed that fires were super intense and they were very destructive. Hearing about other people in the industry that'd been around for longer in the field, they would talk about the trends of fires growing hotter, faster, and harder to fight. Aside from the growth of fire intensity, the trend I started seeing was an unsupported workforce, and I wouldn't say a struggling workforce, but just there were issues around workforce retention that we talked about, and I didn't have a whole lot of faith in the government at the time to switch things around fast enough to address these trends of workforce development and how do we refocus our efforts on mitigation and not just suppression.

(31:58):

That's when I started to see like, "Okay, maybe I need to change gears." Then one of the trends that I'm starting to see is there is a growing investment in mitigation efforts. I don't think it's nearly enough. I think it should be upwards of what we spend on suppression, given how important mitigation is. Within mitigation, I think we really need to figure out ways to thin forest and reintroduce good fire back into the landscape. This is why I'm really excited about my current work for Kodama is because we're pushing the envelope and trying to be a leader in innovation around forest restoration. We're doing that by automating machinery, we're optimizing on the ground operations and we're developing new methods for biomass utilization. All these things are typically challenges for the forestry industry right now on the mitigation and thinning side.

Yin Lu (33:04):

Can you get one level deeper and talk more depth to the degree that you can about what Kodama is actually doing on the ground? I think it's fascinating what you all are working on.

James Sedlak (33:13):

Yeah, so we're trying to learn the ins and outs of different types of operations, and we're trying to improve site connectivity to make operators and machines work more efficiently. It's already an industry that's working off of super tight profit margins, and we're trying to make things better for everyone. Typically, a big challenge for forestry thinning operations is dealing. You have forestry thinning operations that takes marketable timber out of woods, reduces hazardous fuel loads that contribute to wildfires, so you're taking away that wildfire risk, but there's still a lot of excess biomass that's either being left in the woods to burn, or sometimes it just gets forgotten about in it decays. We're exploring a new method of thinking for how do we get that excess waste biomass out of the woods? How do we do something that has value with it? Right now, we're exploring a carbon storage technology to basically take all the excess wood while it has a lot of carbon in it and store in specially-designed vaults. We're pretty excited about that opportunity.

Yin Lu (34:27):

So, two-pronged approach, it sounds like. One is you're helping with the mitigation efforts to compliment what the federal government and state governments are doing by thinning the forest, which is very critical, so you remove all the excess wood that could burn and burn really fast because it's dry, and all the moisture has been escaped. Then on top of that, you take that excess and then put underground to sequester carbon.

James Sedlak (34:49):

Yeah, that's pretty much where we're headed. We believe that within the forestry thinning operations, typically right now, forests are super overgrown and they're unhealthy. You've got trees that are competing against each other. Just the act of thinning is one step to get forests back into, at least western forests that are fire adapted, to get them back into their patchier, more diverse mosaic that are more balanced.

Yin Lu (35:19):

Gotcha. What you all do in Kodama is really two birds with one stone, feed two birds with one scone, depending on what analogy you like.

James Sedlak (35:27):

I like plant two trees with one shovel.

Yin Lu (35:29):

Oh, my God. Okay. That is so much better. Two plant trees with one shovel. Yes. In addition to what you all are working on at Kodama, are there any other technology areas that you're excited about when it comes to fire suppression and mitigation?

James Sedlak (35:41):

Yeah, there's a lot of great work going on right now in the industry. Even from the traditional timber operations side, I I'm starting to see heavy equipment machines that are being adapted for wildfire suppression. It's a big excavator type machines that can carry water on them and extinguish fire with water while also using grapples to dig and maneuver better, and replace the work of certain hand crews and personnel so they can go on to do other challenging tasks and not have to do the simpler tasks. I'm seeing some really cool innovations from traditional, I guess, lumber and timber operators. Then there's a lot of cool technology being developed in, I guess, the private startup space, like early detection systems and drone technology to go put out fires within first, I don't know, 10, 15 minutes of monitoring, and really cool planning and collaboration software.

(36:47):

I think planning and collaboration among different stakeholders has been such a challenge to increase the pace and scale of restoration work because it's so hard to find common ground with different wildlife groups, communities worried about environmental justice, your landowners with their interests. There's just a lot of competing interests, and so having good software and tools to lay all those interests out and map out different progression plans is, I think, really, really cool. I think what's driving a big push for a lot of this technology is really strong science. I think we're getting better at utilizing large data sets that really do a good job of laying out the different conditions of our forested landscapes, whether it be certain habitats of sensitive species, different levels of vegetation, and densities of timber stands, and just assessing the fire risk in certain areas. You put all of those mapping layers together in RGIS, and now you're able to prioritize and see what areas of the land that we need to focus on efforts.

Yin Lu (38:01):

That's awesome. I think what we've covered is you have the surge of new technology that's coming into the space, technology and innovation on the software, and on the hardware side, we have policy tailwinds now that hopefully will get the workforce more developed than it has been because we really, really need it. We have capital that's coming in into the private sector as well as the policy and the things that will bring more capital into from a public sectors, and the need is more than ever. California's been in, was it severe critical drought? I don't forget the technical categorization, but gosh, fires aren't going to stop happening, and so what are we doing to ensuring that we suppress and mitigate better? One last question I have before we go, I know you got to go soon, is we're doing this recording in mid-January 2023, and there has been many atmospheric rivers just coming down on California, just lots of rain, flooding, more rain than we've seen in many years. Any thoughts on the implications that the flooding is going to have on firefighting season this year and for years to come?

James Sedlak (39:06):

Yeah, so I think with the heavy amount of precipitation that we have right now, and perhaps it's trending to be a wet season, that could mean more vegetation growth and hence more fuels down the road for wildfires to burn, so that's one thought that comes to mind. It's great that we're getting precipitation. We've needed it. We've been in a drought in California for a couple of years, a few years now, so I think it's great. It's just something to be cautious of. I think I just feel like we're living in a couple of extremes right now, heavy precipitation, heavy drought, and we just need to keep the implications in mind of what that means for wildfire season, or yeah, wildfire impacts and things like that, but yeah, fire and water have a really interesting relationship, and they're both really powerful natural forces that shouldn't be taken lightly, and so we'll have to see what the summer brings.

Yin Lu (40:03):

All right. Well, with that, man, James, thank you for teaching us so many different nuances of the world that you live in, and thank you, obviously, goes about the same for all the work that you have done and continue to do to help us keep those fires at bay.

James Sedlak (40:18):

Just doing what we can to take care of the land. That's really what-

Yin Lu (40:21):

Yeah, well said.

James Sedlak (40:21):

... what it's all about.

Yin Lu (40:23):

Well said. All right. If you're interested in learning more about the day in the life of a wildland firefighter and see some pictures that James has taken, I'd highly recommended, James wrote a piece on foreign organization called Earth Refuge that you can find online by typing in his name, James Sedlak, S-E-D-L-A-K, firefighting, and it's the first link that comes up. You get to see some really interesting photos and commentary from James, so highly recommend it. Thank you so much for your time, and I look forward to keeping in touch and seeing all the great things that you and the Kodama team are off to.

James Sedlak (40:53):

Thank you, Yin. I really appreciate it, and yeah, it's been a lot of fun.

Jason Jacobs (40:57):

Thanks again for joining us on the My Climate Journey podcast.

Cody Simms (41:00):

At MCJ Collective, we're all about powering collective innovation for climate solutions by breaking down silos and unleashing problem solving capacity. To do this, we focus on three main pillars, content like this podcast and our weekly newsletter, capital to fund companies that are working to address climate change, and our member community to bring people together, as Yin described earlier.

Jason Jacobs (41:23):

If you'd like to learn more about MCJ Collective, visit us at www.mcjcollective.com, and if you have guest suggestions, feel free to let us know on Twitter @mcjpod.

Cody Simms (41:37):

Thanks, and see you next episode.